Calocedrus decurrens

Following the last couple of months’ blogs on Southern Hemisphere conifers, the February instalment is an introduction to western North American conifers in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Many of these trees and shrubs are familiar to Vancouver residents, as a number are southern BC natives—yellow cedar and western red cedar, the common and horizontal junipers, and Rocky Mountain junipers, for example. But further to the south—especially beyond where the Pleistocene glaciers of the last Ice Age terminated—the diversity of this family becomes considerable. It is worth considering that while there are six cypress family members native to BC, there are twenty-one in California. This southern diversity is reflected to some extent in the plantings of the Pacific Slope Garden as well as in the North American section of the E.H. Lohbrunner Alpine Garden. Botanical Garden staff have collected seeds extensively in the Siskiyous Mountains for these areas. The Siskiyous are a highly biodiverse range on the border of California and Oregon where a good deal of the cypress family diversity can be found.

Many of BC’s native conifers, including most of the cypress relatives, can be found in the BC Rainforest Garden. A moderate-sized western red cedar, Thuja plicata, greets visitors beside the education pod (the “Cedar Pod”) near the entrance. As the interpretive signage indicates, western red cedar is known as the cornerstone of northwest coast First Nations culture. First Nations peoples used the wood, limbs, roots and bark to make innumerable products, from masks, boxes, clothing, utensils and cradles to totem poles, houses, hats and ocean-going canoes. Thuja plicata is a valuable timber tree because of its beautiful straight-grained, weatherproof wood. The similar-looking yellow cedar, Callitropsis nootkatensis, is probably second only to the red cedar in BC Coastal First Nations culture. The easily-carved wood is still especially prized for masks, poles and paddles. The two species are readily differentiated by their aromas: western red cedar by the sweet, pineapple-like smell of its handled foliage, and yellow cedar by the strong oregano- and sagebrush-tinged pong of both its wood and leaves. There are several specimens of yellow cedar in the Rainforest Garden. The most prominent is a lovely weeping selection (C. nootkatensis Pendula Group) just inside the entrance.

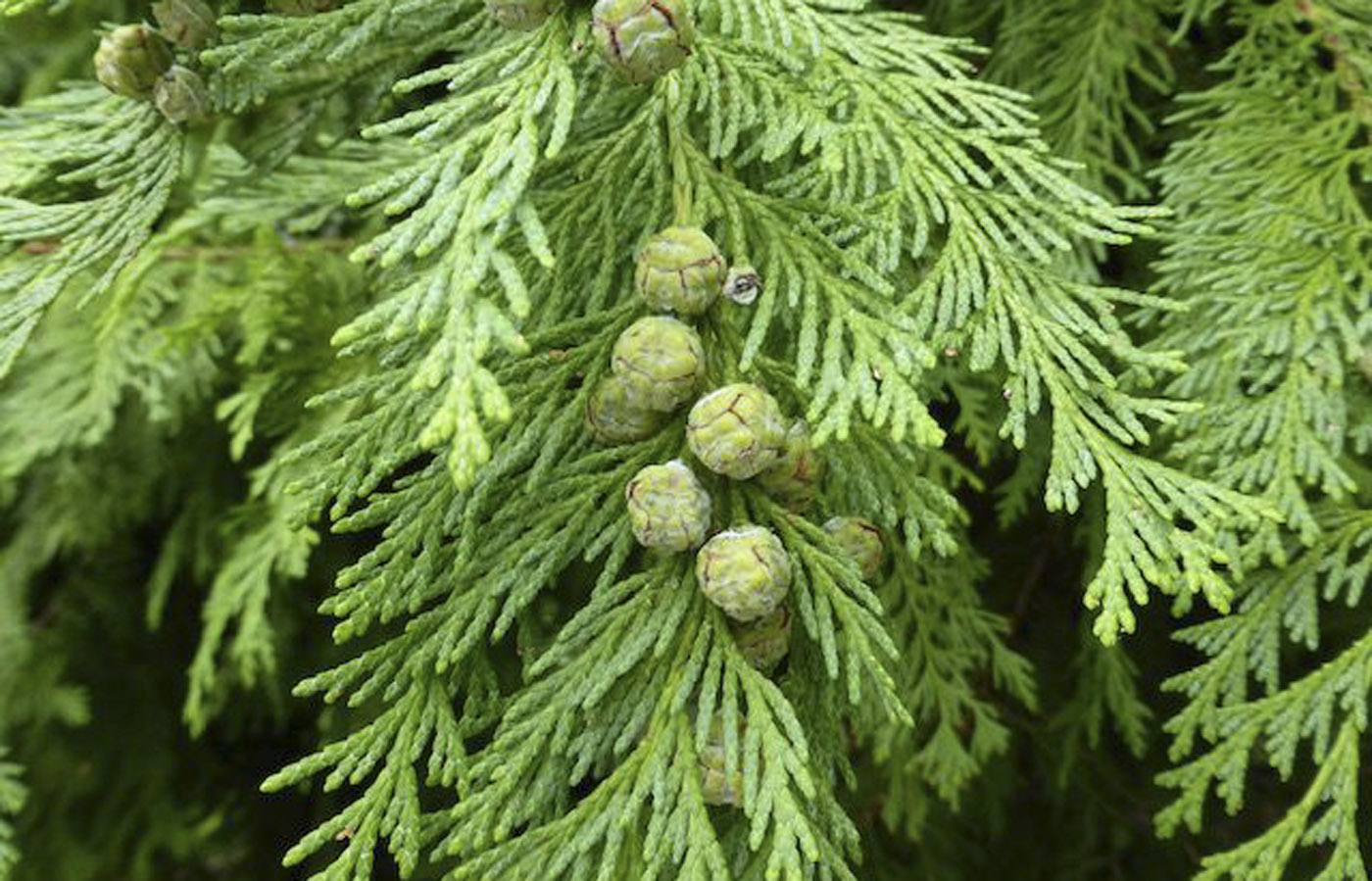

Although not native to BC, Chamaecyparis lawsoniana (Lawson cypress), looks like it might be. This conifer, which has elegantly drooping branchlets of a finer texture than either western red or yellow cedar, is native to the mountains of northern California and southern Oregon. There are a few small specimens near the middle of the Pacific Slope Garden. This species is unfortunately highly susceptible to a root rotting disease both in cultivation and in the wild. Covering some of the same geographies, but extending further south is the California incense cedar, Calocedrus decurrens, an intensely aromatic species that was once harvested on a large scale for the manufacture of pencils. Our largest specimen, which exhibits the classic, narrow-upright habit of this snow-adapted species, sits above the Garry Oak Meadow Garden. Sequoia sempervirens, the coast redwood, needs no introduction for those lucky enough to have seen this lofty conifer in its habitat. For anyone else, my advice is to make plans to do that. Coast redwood is one of the natural wonders of the world—the tallest living organism, and definitely among the most awe-inspiring. Ours is about 10 years old, planted close to the fence in the middle of the Pacific Slope Garden. A mere pipsqueak at 3 m tall.

Junipers are unusual in the cypress family in having separate male and female plants. They are also mostly notably aromatic and notoriously ill-adapted to Vancouver’s climate. Long-time Vancouver residents have seen junipers come and go as landscape shrubs, but the common juniper, Juniperus communis and its varieties are essentially bullet-proof shrubs. Juniperus communis var. communis is unfortunately also practically untouchable, with its sprawling habit and needle-sharp leaves. The cones on this plant (this specimen is a female) are copiously produced. If you are brave enough to handle them, you might detect the smell of gin, as juniper “berries” are commonly used to flavour that liquor. Across the path is the dwarf juniper, J. communis var. depressa (a male selection). Both are collections from southwestern BC made in the 1970s by the then curator of the BC Native Garden, Al Rose. Two European junipers, J. communis var. saxatilis (mountain juniper) and a horticultural selection, J. communis var. communis ‘Sentinel’ (a small, rocket-shaped shrub), are both located in the European section of the Alpine Garden. Rocky Mountain juniper, Juniperus scopulorum is well-known both for its bedraggled appearance (particularly when cultivated at the coast) and its strong off-putting odour. This is a species from BC’s Interior, but its range also extends across the Rockies and south to northern Mexico. Our largest plant is in the bed across the Service Road from the BC Rainforest Garden. In the North American section of the Alpine Garden close to the service road are two selections of Juniperus horizontalis, a prostrate-growing species that normally only thrives away from the coast. Their good health depends on full exposure to the sun and wind and superlative drainage. Similarly, two drought-adapted junipers from the southwestern states, Juniperus deppeana (alligator juniper—named for the scaly bark) and Juniperus occidentalis (western juniper) are recent additions to the Alpine Garden. Both are large, picturesque, long-lived trees where they are native.

Wrapping up the Garden’s western North American cypresses are species in the genus Hesperocyparis. This relatively recently erected genus comprises North American plants that were traditionally included in Cupressus, which now includes only European, North African and Asian cypresses. We grow five species of Hesperocyparis, four of which (listed below) are native to California. The other, Hesperocyparis arizonica (Arizona cypress) is primarily native to Mexico, with small outliers in southern Arizona and New Mexico. We have a smallish plant (grown from wild-collected seed) in the Alpine Garden, and a much older, 7-m-tall tree, the cultivar ‘Silver Smoke’, near the Roseline Sturdy Amphitheatre. Our newest North American cypress addition is a trio of Hesperocyparis abramsiana (Santa Cruz cypress). These small plants join young Hesperocyparis macnabiana (Shasta cypress) and Hesperocyparis sargentii (Sargent cypress) seedlings in the Pacific Slope Garden. Both the Santa Cruz and Sargent cypresses are eventually good-sized trees, similar in scale with Arizona cypress. In contrast, Shasta cypress remains shrubby, but is known to be among the most resinous and aromatic of all cypresses. Hesperocyparis bakeri (Siskiyou cypress) are also planted in the Pacific Slope Garden in a range of sizes, though our largest—a 20-year-old specimen—is located in the Alpine Garden. Note also that the large hedge that surrounds the Service Yard is made from the exceptionally versatile ´x Hesperotropsis leylandii (Leyland cypress), which is a hybrid of two western North American cypresses: Hesperocyparis macrocarpa (Monterey cypress) and Callitropsis nootkatensis (yellow cedar).

Submitted by: Douglas Justice, Associate Director, Horticulture and Collections

- Callitropsis nootkatensis Pendula Group

- Callitropsis nootkatensis Pendula Group

- Calocedrus decurrens

- Callitropsis nootkatensis Pendula Group

- Calocedrus decurrens

- Chamaecyparis lawsoniana

- Chamaecyparis lawsoniana

- Calocedrus decurrens

- Hesperocyparis arizonica

- Hesperocyparis arizonica

- Hesperocyparis arizonica

- Junipers communis

- Hesperocyparis bakeri

- Hesperocyparis bakeri

- Hesperocyparis abramsiana

- Hesperocyparis macnabiana

- Hesperocyparis sargentii

- Junipers communis Saxatilis

- Junipers communis var depressa

- Junipers communis var depressa

- Junipers communis var. saxatilis

- Junipers communis

- Junipers communis

- Juniperus deppeana

- Juniperus horizontalis Grey Forest

- Juniperus horizontalis Heart Butte

- Juniperus occidentalis

- Junipers communis var depressa

- Juniperus scopulorum

- Sequoia sempervirens

Hi Ron, I reached out to Douglas Justice and shared your blog post response and he has replied to you here:

Regarding the junipers in this article, we have a number of wild-sourced Juniperus communis plants in the garden with a variety of names attached. Their taxonomy has been neglected for years (and I admit to putting off doing my homework here). This is a confusing group and there is much in the literature that is confused and misleading with respect to naming. For example, there is only partial agreement between Flora of North America and Plants of the World Online. A thorough review is clearly in order.

Regarding the cypresses, I would definitely prefer to be using the classification outlined on D. Earle’s page (https://www.conifers.org/cu/Cupressus.php), as it is straightforward and appears eminently sensible. Unfortunately, it’s not based on the most up-to-date research. The need to split the group follows a 2022 paper (see Recent advances on phylogenomics of gymnosperms and a new classification, by Yong Yang et al., Plant Diversity 44 (2022) 340-350), which pretty much upsets the whole Cupressus apple cart.

The Yang et al. paper reveals that Cupressus as traditionally circumscribed is actually represented by two distinct clades (branches) on the family tree: a Eurasian-African clade with about eight species, and a western (strictly North American) clade (Hesperocyparis) with about a dozen species. Uniting them all under one broadly-defined Cupressus was not possible once it was also discovered that the Eurasian-African branch is more closely related to Juniperus than to Hesperocyparis, while Hesperocyparis is more closely related to Callitropsis nootkatensis (yellow cedar) and Xanthocyparis vietnamensis (Vietnam yellow cedar) than it is to the Old-World cypresses. The alternative (if one is to maintain monophylly) is to lump all of the species, including Juniperus, into one genus. I would happily recant if someone proves that the work by Yang et al. is flawed.

Here is the relevant passage from the paper:

2.5. Relationships of the Callitropsis-Cupressus-Hesperocyparise-Xanthocyparis complex

Farjon and his collaborators described a new genus collected from Vietnam, i.e., Xanthocyparis Farjon & T.H. Nguyen (Farjon et al., 2002). The nomenclature of this genus and subsequent molecular systematic studies resulted in debates and taxonomic chaos within Cupressus L. and related genera (Farjon et al., 2002; Little, 2006; de Laubenfels, 2009; Zhu et al., 2018). Farjon et al. (2002) included Callitropsis Oerst. in the genus Xanthocyparis, i.e., Xanthocyparis nootkatensis (D. Don) Farjon & Harder. This inclusion made the name Xanthocyparis superfluous and illegitimate in nomenclature. For further use of Xanthocyparis, Mill and Farjon (2006) proposed to conserve Xanthocyparis against Callitropsis, and the nomenclature committee accepted their proposal (Brummitt, 2007). Little (2006) constructed a phylogeny of Xanthocyparis, Callitropsis, and Cupressus s.s., and found that Cupressus is diphyletic; he thus treated Xanthocyparis, Callitropsis and the New World Cupressus as a single genus. He adopted Callitropsis s.l. as the correct generic name and made a number of new combinations. But phylogenetic relationships among these generic clades were not resolved in that study. Christenhusz et al. (2011) took a conservative option and incorporated Xanthocyparis, Callitropsis, and Hesperocyparis Bartel & R.A. Price into Cupressus, which is paraphyletic with respect to Juniperus (Mao et al., 2019). Terry et al. (2012), Zhu et al. (2018), and Mao et al. (2019) resolved the phylogenetic relationships of these genera and recognized Xanthocyparis s.s., Callitropsis s.s., Hesperocyparis (New World Cupressus) and Cupressus s.s. (Old World Cupressus). Callitropsis s.s. and Xanthocyparis s.s. do not form a clade in these recent phylogenies; thus, Farjon’s incorporation of Callitropsis s.s. into Xanthocyparis s.l. is untenable.

See discussion of Cupressus taxonomy here:

https://www.conifers.org/cu/Cupressus.php

Dr. Earle has also produced an updated treatment of Juniperus communis, see his page on this species on the same web site.