An Expedition Blog

Day 1 & 2, Hanoi to Sapa: Andy Hill (Curator-Horticulturist, David C. Lam Asian Garden) and I arrived at Hanoi International Airport following uneventful flights from Vancouver and Hong Kong. Hanoi airport is surprisingly large, presumably to accommodate the huge number of tourists coming to Vietnam, but the layout is essentially linear, which means that it can be a fairly long walk to the main part of the terminal. This was actually a welcome prospect after being wedged into small airline seats for most of the night and part of the morning. We met Dan Crowley, dendrologist at Westonbirt Arboretum, at the baggage carousel—he had arrived some hours earlier from a direct flight from London—and proceeded out into the arrivals area. Nguyen Van Du and Bui Hong Quang, our botanist colleagues from the Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources (IEBR) in Hanoi, met us as arranged, and we all piled into a borrowed SUV and headed for Hanoi. The weather there was about as pleasant as it can be: not too hot, but humid, with a bright grey-white sky and an ever-present mist in the distance. There is a measure of smog in this, but I prefer to think of it as mist, as I’m breathing it. The Danly Hotel is close to the university and conveniently close to both the airport and the institute. It was a pleasant enough hotel, but on a busy thoroughfare with the constant honking and thrumming far into the night that that usually involves.

Navigating the intense Hanoi traffic

Andy, Dan and I had a leisurely breakfast in the hotel before setting off on a walk through the local neighbourhoods. From my thirteenth floor room, I could see a park and what appeared to be zoo enclosures off to the south. We skirted the zoo—none of us was particularly interested in looking at caged animals—walking down labyrinthine alleys and streets filled with vegetable and meat vendors, the larger stalls on larger lanes and bigger shops with dry goods, as well as restaurants, hairdressing salons, motorbike retailers, furniture makers and coffee shops. To my western eye, the traffic is chaotic: there is a relentless pulsing of motorbikes, cars, buses and trucks through the narrow streets, but paradoxically, a surprisingly smooth flow of weaving and dodging of people and machines at the merges and crossing points. Other than at traffic lights there is virtually no stopping of vehicles. The number of motorbikes and the uses to which they are put is almost unfathomable. Families—mom, dad, child and baby—are common on scooters, but so too are women passengers in skirts riding side saddle, riders balancing credenzas, tables, engine parts, giant bamboo poles, sheet metal, bundles of rebar (the ends bobbing and nearly grazing the ground 4 m ahead and behind), crates filled with chickens, ducks, rabbits or pigs, and baskets strapped to baskets overflowing with sacs bulging with plastic bottles, bags and other recyclables. The extraordinary thing is that despite the volume there seems to be few mishaps of any kind on the roads. We walked for a couple of hours, taking much of this in before getting back to the hotel where we met Du and Quang, and the rest of the entourage from the IEBR, the Master’s students, Bing and Sung.

Our next stop was a phở lunch, then to the airport to pick up Heronswood director Dan Hinkley (plant explorer extraordinaire). The ride to Sapa was in a limousine-van, tricked-out with all the comforts: plush, reclining seats, a bar with phony crystal glasses (though there was no free booze in evidence), a television screen, USB ports at every seat, and tinted windows with pull-down shades. Unfortunately, there was barely enough room for the eight of us and our luggage, so it was a very tight squeeze. The road to Sapa, about five hours north of Hanoi, is a divided highway for most of its length, but the mountainous portion is narrow and increasingly steep and tortuous as it approaches Sapa, with older buses and innumerable huge transport trucks labouring up the steeper hills. Passing is a skill and an art, especially when travelling up hills on blind corners in thick fog, and I have to admit I was mystified how our driver knew when it was safe to pass.

On arrival, we were greeted enthusiastically by our hotelier and mountain guide, Uoc Huu Le, and Crûg Farm Plants owner and plantsman Bleddyn Wynn-Jones, who had arrived a few days prior. Also in attendance at the hotel was the bulk of the group of porters who would be packing and carrying our gear and supplies over the next ten days. The porters are all Hmong, an ethnic group common to northern Vietnam and adjacent southwestern China, Cambodia and Laos. Evidently, Uoc’s father was ethnic Hmong, while his mother (whom we met on our previous visit in 2016) is Kinh, the majority ethnic group in Vietnam. Now in his forties, Uoc has been leading expeditions in the Sapa region for decades. He first met Dan Hinkley as a seventeen year-old guide on Dan’s first trip to Vietnam. Sue and Bleddyn Wynn Jones also took advantage of Uoc’s skills as a guide, as did Peter Wharton, the late curator of the David C. Lam Asian Garden, though some years later. Uoc’s hotel, The Mountaineer, is modest, but well-appointed and comfortable. We were planning to head out first thing in the morning to hike the mountain known as Five Fingers. This was anticipated to be an exceptionally challenging four days of hiking, and for that reason, Uoc had had a pig killed and butchered for our dinner. The meal was somewhat challenging for most of us (the Westerners, at least). There were few vegetables, some tofu and fried egg prepared for Andy, who is vegetarian, but little other than energy-rich, very fatty pork for the rest of us. As it turned out, we needed all the energy we could muster over the next few days.

Surviving the vertiginous slopes of Five Fingers

Day 3-6, Five Fingers: To be honest, the four days we spent on Five Fingers kind of blurs. Every day was a series of steep ascents and descents, the tracks at times hardly recognizable as trails. Our route was frequently exceptionally precipitous, and often dangerous if you weren’t paying sufficient attention. The worst times for me were usually late in the day, when a numbing kind of fatigue had set in after hours of serious exertion. When so drained, I constantly slipped and tripped and barked my shins negotiating the steep down-slope trails. It was not so much galling as bewildering that the porters, who were loaded down with 30- or 40-kilo baskets and wearing rubber boots or plastic sandals, could descend vertiginous slopes with a steady, unhesitating gait, while I was clinging to branches and roots, often having to sit and skid on my bum or even turn around and feel my way slowly to where my feet found safe purchase. My confidence was undermined by the gradual loss of leg muscle stability (the knees becoming more or less rubbery with the constant jarring) and a few slips and falls; there was little hope of regaining balance or indeed, my composure. It was unnerving. At one point, I caught my shoe on something and would have tumbled some considerable distance (to where, I know not) if I hadn’t pointed myself into a sizable tree. My chest and the tree trunk met suddenly. It thankfully stopped my fall, but I bruised a rib painfully in the process. It was at that point that I started thinking wistfully about my upcoming Hawaiian vacation. Rather than depress myself by dwelling on my own physical shortcomings, I took some comfort in knowing that the fitness level of my travelling companions was much greater than mine, and that they would be there to carry me out should I need any kind of assistance.

The upside of the hike was that the views were often spectacular and the areas so steep and inaccessible that there was little in the way of cardamom cultivation or tree removal for that or other purposes. (About a decade ago, cardamom replaced opium poppies as a cash crop for the hill people. With the sanction of the government, farmers plant this ginger relative extensively in the mountains, including in the national parks. Cardamom is best cultivated on cleared, sloping land where conditions are cool and moist and somewhat shaded.) It seemed at times that we were quite alone, and the wilderness more or less pristine. The main purpose of this trek and our time in Vietnam in general, was to catalogue the exceptional diversity of plants we saw, and to collect samples to be pressed for herbarium specimens. We collected as many plants as we could that were in flower or fruit, including ferns with spores. Secateurs were used for plants within reach, while a long-arm cutter was employed for samples up to about 4 m away. Larger trees with reproductive structures or epiphytes high in their canopies, or plants on cliff faces or similarly inaccessible sites conjured discussions of drones with cutters and graspers. Maybe next time?

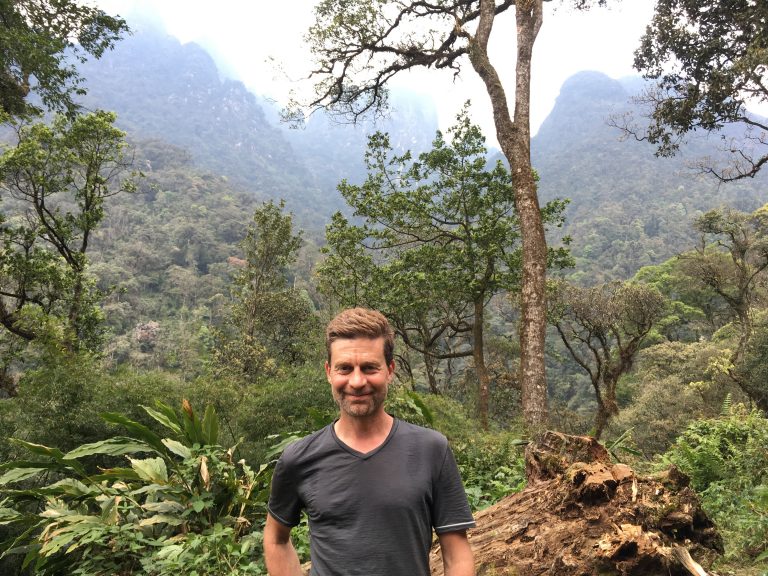

Douglas Justice examining an Acer species

Notwithstanding concern about my own well being on the trail, the remarkable diversity of plants, the various floristic assemblages and our physical collections is where my mind was focused most of the time. To be frank, though, it was our Vietnamese colleagues who identified the vast majority of material worthy of collection along the trail. Even when I wasn’t watching my feet, I missed the majority of what they could select out of the forest. It was actually quite surprising what they seemed to be able to see. I would stand and scan the forest up and down, seeing nothing in flower or fruit, then move on, only to hear some considerable activity behind me. They’d made not one, but multiple collections! On the other hand, I’m particularly interested in Acer species (maples), and these I could generally pick out without difficulty. This interest was shared to some degree by others in the group, especially by Dan Crowley, who has significant expertise in the subject. He and I spent considerable time and energy on collecting Acer material, but also in discussion about Vietnamese maples in general—probably to the point of excess for some of our colleagues. I should add that the porters, although happy to help collect material for us, were basically only interested in food plants, and we regularly ate vegetation of one kind or other that had been collected along the trail.

The collections were numerous and varied, depending on where we were on the mountain: whether in sun or shade, or in a moist, dry or exposed sites. Much of the material could only be identified to family or genus. Some things were obvious, such as maples, gingers, primulas, rhododendrons, aralids and magnolias, but many of the plants were members of tropical families and less familiar to us. For each plant collected, four samples were taken: one each for the herbariums at UBC, Oxford, IEBR and the Hoang Lien Son National Park. Each collection was photographed, given GPS coordinates and individually tagged, and its floristic associates recorded before being carefully packaged up in newspaper then compressed in the portable press. The students from the IEBR, Bing and Sung, were skilled at processing the samples. Even still, we were often an hour or so behind the porters and those not involved in collecting. One advantage of stopping regularly, however, was that it made for a comfortable hiking pace; another was that we would amble into the midday lunch site with the food already laid out, or the campsite at the end of the day with the tents already set up.

In general, our campsites were not really campsites, and although the porters looked for level ground, we seldom had ideal conditions for tents, or room for sitting around. In a couple of cases, the tents were spread out fairly widely and at some distance from the food preparation area. On one occasion my tent was perched right at the edge of a cliff—the back door one step away from the bottom of the valley. Most of us started the days with stories of fitful sleeps with sore hips or backs, or of struggling against constantly sliding to the low side of the tent, but breakfast usually erased any negative thoughts. The porters were as adept at making delicious meals as they were scaling mountains. Breakfast was either French-style crepe with honey, banana and mango, or noodles and egg in broth—surprisingly delicious considering they were “instant” noodles. And while lunches were generally forgettable, do-it-yourself affairs with bread, sliced cucumber and tomato, those little packaged triangles of cheese, dried pork fluff and some spam-like meat product, or sticky rice with peanuts, dinners were invariably spectacular five- or six-course affairs. These consisted of fresh chicken and a variety of locally foraged and transported vegetables, pork, tofu, soups and perfectly cooked rice (how do they do that on a wood fire?). All of the food was surprisingly good and we definitely felt spoiled.

Andy Hill stopping to enjoy the view on Five Fingers

When we finally descended Five Fingers, we were all pretty beat. The last few kilometres followed a largish, boulder-strewn creek, which we had to ford several times. Despite the more or less gentle grade, this was fairly challenging, as some parts of the stream were impassible and the trail headed back into the forest, often considerable distances to avoid these places. Inevitably, where we crossed the water was deep and the boulders slippery, and not always well placed for hopping across. There were a number of missteps: some minor, resulting in wet boots, and a couple of more serious slips, ending in partial dunking, but nobody was badly injured on this or any other part of the trail. We were exceptionally lucky that it hadn’t rained—not least that the steeper trails would have been dangerous and the low spots muddy, but it would have meant high water in the creek, and that would have necessitated wading in places. This leg of the trek was surprisingly hard work and because we were now at a lower elevation, the temperature was high enough to be uncomfortable. With the end of the trail nearly in sight, we came upon a small beach next to a deep pool. Three of us stripped down to our skivvies and waded in to the chilly water. There’s nothing quite like cooling off in a mountain stream. Bliss! On the other hand, there’s nothing like having a hot shower after a four-day hike and a cramped van ride back to the hotel in Sapa.

Day 7-9, Y Ty: Five Fingers was a challenging mountain, and we felt it would be hard to match the experience or exceed the incredible plant diversity that we had sampled there. We were wrong about the diversity. The next day we headed off to Y Ty, joined by Scott McMahan from Atlanta Botanic Garden, his colleague at the University of Georgia, Donglin Zhang, and Bleddyn Wynn-Jones. We had visited the mountain the year previous and had been impressed, but it had been a cold winter and a slow spring, and this year we arrived two weeks later, following a mild winter. This time, plants were much further advanced in leaf, and there were considerably more flowers to see. It was simply incredible at nearly every turn. We spent two nights on Y Ty. On the second day we hiked toward the summit, making collections on the way.

Vietnamese flowers were spectacular this spring

This was challenging not only because it was steep, but because the vegetation across a broad swath of the mountain had recently been cut down to make room for cardamom plantings. We were basically walking through a giant slash pile. Being careful to avoid tripping over the cut brush, I caught my foot in a gap between some buttressed root flanges of a beautiful tall tree I was admiring, and fell hard, twisting my ankle. Talk about repeating last year’s mishap! From this point I mostly hobbled my way back to camp, kicking myself (figuratively) for my carelessness. Even still, there were plenty of plants to ogle and I had to be extra careful to stop before scanning for interesting ones. And in any case, our most productive collection area was actually on the lower slopes of the mountain, close to the campsite, and below, descending toward the road (between 1800 m and 2200 m).

The diversity of tree species in particular in this area, was astonishing. A few of the botanical highlights: five different maples, the rare walnut-like Rhoiptelea chiliantha with its whisk-like seed clusters (previously collected by Peter Wharton), and the cherry-look-alike Dipentodon sinicus. This last tree we all puzzled over for days. Dan Crowley actually correctly identified it, recalling a plant he’d seen in a Cornish garden that he thought might be a match, but he ultimately deferred to the botanists in the group, who, myself included, were basically mystified.

Leaving Y Ty wasn’t easy, mostly because it’s nice to linger in a place so richly endowed with amazing plants. However, there is also a bitter-sweetness about the place, knowing it’s not officially protected and that the biodiversity is imperiled. Fortunately, our Vietnamese partners at the IEBR are pushing ahead with the idea of an ecological reserve, and have already started interviewing the resident families in the area. The families that live here need to be able to farm to produce food, but they need a source of income, too, and this currently comes from cardamom, timber, a small fish farm and plants foraged in the wild. Any solution that will afford protection to the biodiversity on Y Ty will have to take the residents’ livelihoods into account as well.

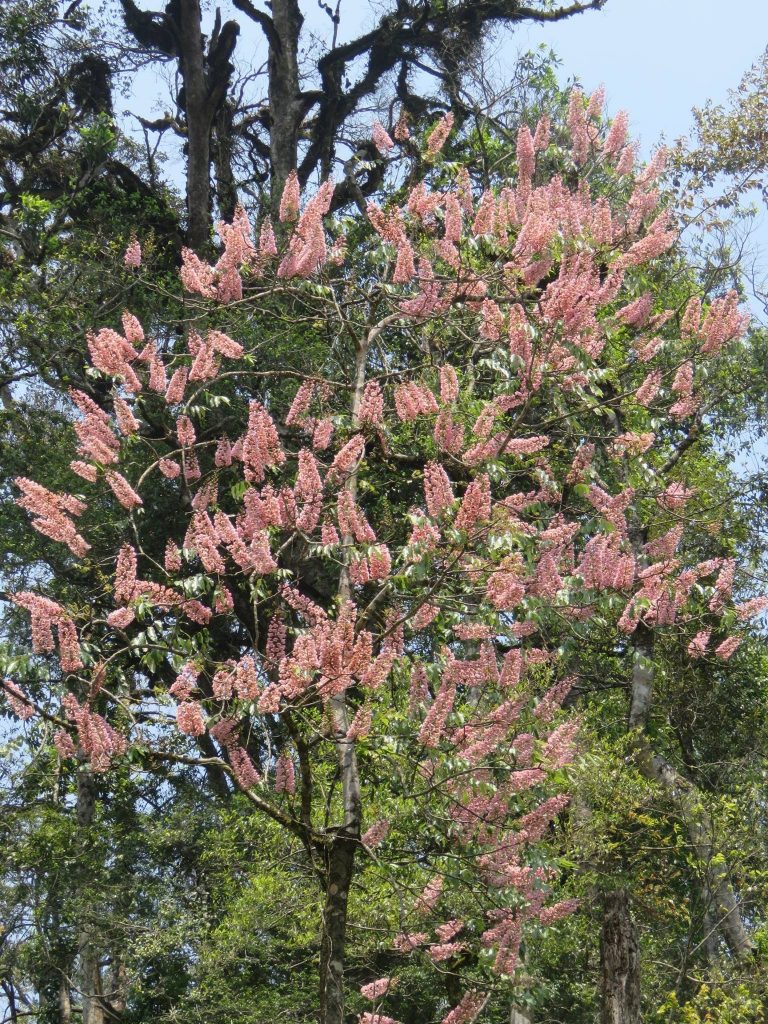

Bretschneidera sinensis

We finally loaded up and headed back to Sapa, most of us still giddy with visions of rare plants dancing in our heads. It wasn’t more than a few kilometres down the road and still very much in the vicinity of Y Ty that Scott suddenly yelled “Stop the car!” Uoc stopped the van and we all piled out and walked back up the road to see what he had thought was so important. I thought perhaps he’d seen a tiger or a monkey—both long extirpated from this part of Vietnam—but it wasn’t either of those. Across a small creek and at the base of a steep hill was a tree, perhaps 25 m tall, straight and unbranched for most of its height. The canopy of branches was nearly obscured by gigantic conical inflorescences that appeared to be comprised of large, bright pink flowers. It was quite a sight—magnificent, really—and I could see why Scott had noticed it as we hurtled by. Dan Crowley had seen the same tree on the way up, and he mentioned it to me at the time, but our driver was not in any mood to slow down. We all stood there somewhat awestruck and puzzling away. Someone picked up a flower and then it occurred to me that we were looking at a particularly spectacular Bretschneidera sinensis, an exceptionally rare tree native across southern China, adjacent Indochina and Taiwan. The IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) Red List states that the species is “uncommon and thought to be getting rarer” and the “…population in Viet Nam is considered to be threatened.” Even in a place as rich as Y Ty, we saw this tree only once, here, in this place. Who can say whether it will be cut down next week for its strong, straight-grained timber. It seems to me that this tree should surely be a protected species.

Day 10-11, Back to Hanoi: Our final excursion before returning to civilization was to the mountain known as Tam Dao, which is about an hour north of Hanoi. Our purpose here was to see Acer heptaphlebium (the seven-veined maple). This name (A. heptaphlebium) has been associated with an exceptionally attractive maple common to higher elevations in the Hoang Lien mountains. This maple, which is allied to Acer campbellii, is exceptionally attractive and much sought after as a garden plant. In fact, we have a lovely specimen here at UBC Botanical Garden. Once we found the true A. heptaphlebium, however, we could see that the two maples are not closely related. It was satisfying to check this maple off our list, and to be able to unravel some of the confusion. Now, of course, we’ll have to change the label on our plant in the garden (but to what?). Coming back down the mountain we pulled over at a roadside temple, where Du recommended we stop to listen to some music. We entered the temple where it was obvious that more than a concert was taking place. Here was a very loud Taoist ceremony with people in colourful costumes playing instruments and darting to and fro around rows and rows of paper effigies (people, horses, ships, etc.). Our timing was perfect, as within minutes of us arriving the ceremony culminated in the effigies being tossed (with enthusiasm) into a great fire pit.

The following day we visited the IEBR herbarium (herbaria are where dried, pressed, labelled plant samples are housed) and spent some considerable time going through the Acer collection. Viewing all of the herbarium specimens was illuminating, but it also raised as many new questions as it answered. It might seem incredible, but the relationships between the various maples, their distributions in Vietnam and even their legitimacy as species is not well known. And that’s just the maples! Hard work ahead.

It takes a huge team to carry off these expeditions; thanks to everybody who made it possible!

Submitted by Douglas Justice, Associate Director, Horticulture & Collections, April 25, 2017

Hi Douglas Justice

My apologies for only catching up with your blog today. Your blog has proved to be very enlightening.

What a great expedition, what a remarkable place, and what unbelievably stunning plants.

I congratulate you and all your intrepid colleagues, both UK and Vietnamese, for such wonderful work.

Here’s to greater plant awareness and flora conservation.

My best wishes,

Anthony Curry 17/10/2023

Hi Andrew, unfortunately the garden which is mentioned is a private estate. Sorry we aren’t able to share further details.

I was interested to read of your sighting of Dipentodon sinicus, having seen it earlier this year on a botanising trip to Yunnan. Do you recall in which Cornish garden Dan Crowley has seen it as I would like to source some seed and try to grow it.

Thanks

AndrewR

Thank you Lucy! Douglas & Andy enjoy sharing their stories of their expeditions and are glad they could bring back so many memories of Vietnam for you! (Hmmm, Borneo…will have to think about it!)

Hi Justice,

Thank you! for your great description about your field trip to Vietnam. My husband and myself enjoyed it very much, and brought back memories from the years we used to live in Vietnam. Reading it feels like living the experience.

Personally I love the North: the people, and Hmong People are very kind, the landscape and the food and of course the richness of the flora.

At the time when we were there the road from Hanoi to Sapa was almost empty! only bicycles and pigs, or ducks crossing the road. Hanoi was not congested, just bicycles, very few cars, and motorbikes start to come out!

We were stationed at the border with China in the north.

Thanks again, and all the best with your great work! ..(Have you think about going to Borneo?)…

Best wishes,

LN