Endangered Maples in Southern Japan – March 14 – March 28, 2024

Sasa veitchii

The trip participants were Dan Crowley (Westonbirt Arboretum, UK, and BGCI), Ikuyo Saeki (University of Tsukuba, Japan), Ryo Sugiyama (Nitobe Memorial Garden) and Douglas Justice (UBC Botanical Garden). Ikuyo joined us on Day 2, on our way to the Ryukyu Islands, and left us on Day 10, so that she could attend the university graduation of her students.

Tokyo. On our first full day in Tokyo, we visited the Institute for Nature Study, a protected forested park in the middle of the city. Managed by the National Museum of Nature and Science, the area is truly a green oasis and is both a Natural Monument and National Historical Site. Garden highlights included a number of venerable trees, some planted more than 400 years ago. Many of the deciduous trees were unrecognizable at these unfamiliar dimensions, especially as they had not yet leafed out. For example, the little-known cannabis relative Aphananthe aspera—little-known because it is usually an unremarkable looking tree—displayed rather distinctive (and remarkable) shaggy bark as an older specimen. We were most impressed by several Pinus thunbergii (Japanese black pine), as they showed a stunningly thick, fractured bark that only occurs after several hundreds of years of development.

Next on our schedule was a visit to Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden, a large park in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, which is managed by the Ministry of the Environment’s Nature Conservation Bureau. We were met there by Makoto Suzuki (Professor, Tokyo University of Agriculture, and Landscape Architect), who had recently visited us in Vancouver. Among other international projects, Dr. Suzuki is known for his work with the Japan-U.S. Cherry Blossom Centennial Executive Committee (2012 was the 100th anniversary of the ceremonial planting of Japanese flowering cherry trees along the Tidal Basin in Washington, DC). Joining us following a picnic lunch under still-blooming Prunus mume (Japanese apricot) trees, was the National Garden’s Director, Kazuo Somiya, and its knowledgeable Manager, Shihoko Ishihara. Ms. Ishihara had prepared a printout of the garden’s collections for our tour (in Japanese), so that any tree of interest was quickly identified.

Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden is famous for its elaborate chrysanthemum displays in autumn and especially for its huge ornamental cherry collection. There were several cherry trees in bloom—nearly all of them cultivars unfamiliar to me—but then, we were definitely on the early side of cherry blossom viewing. Still, the crowds were substantial and those trees that were in bloom, such as the spectacular, bright, rich-pink-flowered Prunus campanulata (Taiwan cherry) were mobbed by visitors taking selfies.

Cherries aside, the garden is well known for a few substantial tree species, most notably, the vast row of Ginkgo biloba that marks the northern perimeter, individuals of which are estimated to be more than 300 years old. Remarkably, these gigantic trees are pruned annually to keep them looking tidy (and also, perhaps, to keep the females from producing their foul-smelling seeds). Similarly, the 160-some Platanus x hispanica (London plane) that make up the multiple allées of the French Garden are cut hard every year to create a startling and most unlikely picture (for a Japanese garden) of symmetry and grandiloquence.

Platanus x hispanica

Luckily, for those of us who are fans of the unpruned, that category is equally well represented in Shinjuku Gyoen. Their oldest Acer buergerianum (trident maple) in particular, a species we know in Vancouver as a smallish tree, surprised us all by its enormity and character, as did a gigantic ginkgo and a stupendous, multi-trunked London plane. And while the bulk of cherry blossoms were yet to emerge, the sumptuous white flowers of the yulan magnolia, Magnolia denudata, were at the peak of perfection across the park. Each attracted crowds of adoring gawkers. Several strapping Zelkova serrata (keaki) were in evidence in the garden, but one massive specimen, mostly broken, but still with healthy stems and reputed to be more than 400 years old, definitely stood out from the rest. Despite attracting no apparent adulation from passing visitors, the six of us were mightily impressed.

At a somewhat smaller scale, three particularly iconic images stand out for me. One is of the Tagyoushou (Tanyosho) pines, Pinus densiflorus ‘Umbraculifera’ that are scattered across the open rolling landscape near the middle of the park. Old trees, they display wide, umbrella-like crowns and orange-brown bark on all of their stems. The warm-season turf grasses that vegetate the open spaces beneath are completely dormant and straw-brown at this time of year, creating for a Vancouverite, a somewhat confusing summer-like scene. The second is the impressively large planting of Stachyurus praecox var. matsuzakii, a rare, endemic variant of early stachyurus from the Izu Islands south of Tokyo. Stachyurus are normally scandent shrubs; that is, they have long arching stems that loop over the branches of trees or other high objects, allowing them to climb. These plants were growing unsupported, and shaded on one side such that they formed a broad curtain of pendulous flowers toward the light. Finally, we were allowed access to an area at the northeast corner of the park where a historic Japanese garden was being restored. Here stood a group of 300-year-old Taxus cuspidata (Japanese yew), their low, cushion-like clumps of foliage running down slope, with a single jutting, angular stem creating the appropriate visual tension.

Amami-Oshima. We were greeted on arrival to Amami Island with roadside specimens of Pandanus odorifera (syn. P. odoratissimus), the fragrant screw pine, which is native to much of subtropical and tropical Asia. Named for its overlapping spirally-arranged leaves, Pandanus are more closely related to palms than pines. Fruiting plants were common at the Amami Airport, as well as naturally, by the sea above the tide line. Many Pandanus species exploit similar beach habitats. All have curious-looking stilt roots that act to anchor the plants against shifting sand dunes or storm-surge-inundated soils. Away from the beach, Amami’s flora is rife with exotics familiar to any who have visited vacation resorts in Mexico or the Caribbean. Araucaria heterophylla (Norfolk Island pine), Handroanthus chrysotrichus (golden trumpet tree), Alpinia zerumbet ‘Variegata’ (variegated shell ginger), Erythrina speciosa (coral tree) and the shrubby Codiaeum variegatum (croton) with its the multicoloured leaves, all line roads and residential neighbourhoods.

Ficus microcarpa and Cycas revoluta

Ficus microcarpa (Chinese banyan), Cycas revoluta (sago palm) and Cordyline fruticosa (ti plant) are everywhere, and native to the islands. Sago palm, which is not a palm but a cycad, is especially abundant, and despite its considerable toxicity, still cultivated for its starchy pith and seeds (the pith is ground and repeatedly washed to rid it of toxins, then dried). Unfortunately, these cycads are in precipitous decline throughout the southern Japanese islands because of infestations of the cycad aulacaspis scale, and we saw plenty of damage from this exotic insect pest. Another common native here is Ternstroemia gymnanthera (Japanese ternstroemia), which is also found from China to the Himalayas (and which barely survives on the west side of the Campbell Building in UBC Botanical Garden), and noted for its brilliant red spring growth. Likewise, native Asplenium nidus (birds nest fern) and Cyrtomium falcatum (Japanese holly fern) were everywhere on shaded walls and slopes. Large native evergreen azaleas, including selections of Rhododendron indicum, R. kaempferi and R. simsii (and their hybrids) were common as mass plantings and hedging.

Amami Island is geographically and climatically about halfway between Kyushu (the southernmost island of “mainland Japan”) and the island of Okinawa in the island chain known as the Ryukyus (or in Japanese, Nansei-shoto). Amami is one of four islands that make up Japan’s latest UNESCO World Heritage Site—to be precise, there are five sites on parts of four islands, including Amami, that make up the UNESCO site. The actual protected area on Amami comprises 11,640 ha (about 45 sq. mi), with 14,633 ha (55.5 sq. mi) of buffer zone. According to UNESCO, the site “contain[s] the richest biota in Japan, one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots.” As the islands have been more or less isolated for millions of years, there are significant endemic and rare animals and plants.

Thus, it was with some significant anticipation that we embarked on our journey to the site of the endemic, critically endangered Acer amamiense. Indeed, this was initially the principal reason for traveling to Japan. Our goal was to assess the conservation status of A. amamiense and its relationship to the closely-related A. diabolicum. Acer amamiense was said by at least one observer to be restricted to a single site, with fewer than 20 individuals, and no female trees. We discovered, however, that the original assessment was in error. We identified a number of reproductively mature individuals, including three females, some smaller saplings and a few seedlings. Of the three, one lone female tree, together with hundreds of seedlings, mostly scattered across a couple of acres of extremely steep terrain (my calves burned for days after), were new discoveries. While the known extent of the species has been expanded it is still incredibly restricted, and the numbers are concerning. There is also some uncertainty about ownership of the land on which the plants are growing (this area is not part of the UNESCO World Heritage site). As for this maple’s relationship with A. diabolicum, the two species are readily distinguished. There are significant differences in leaf vestiture (hairiness), and as we observed, A. amamiense flowers have bright yellow-green sepals and are borne on pale, silky-hairy stalks, while those of A. diabolicum, a more northerly species, are borne on reddish, nearly hairless stalks, and have a calyx of dark red sepals.

As noted, the Ryukus flora in general, and that of Amami Island in particular, are exceptional. Besides the usual well-known exotics and widespread Asian species are scores of less familiar, but no less intriguing plants. Hoya carnosa (wax-flower vine), well-known to indoor plant growers, was a surprise as an epiphyte on a gigantic Ficus microcarpa. Rhododendrons (particularly the cultivated azaleas) are common constituents on the island, as elsewhere in Japan, but we also saw the comparatively rare, native Rhododendron scabrum, which is a large, red-flowered evergreen azalea, the tree-like Rhododendron amamiense (sacred Amami azalea) and the delicate Rhododendron tashiroi (sakura azalea).

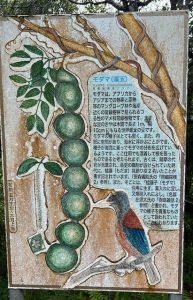

We visited the site of the evergreen climber, Entada phaseoloides (matchbox bean) one exceptionally rainy morning. Endangered on Amami because its numbers are extremely limited there, the species is actually widespread in humid lowland tropical forests across mainland Asia, Melanesia, northern Australia and the western Pacific. Climbing legumes are a dime-a-dozen in the tropical world, but the E. phaseoloides we saw have centuries-old twisted and polished woody stems more than 30 cm thick. The 6-cm wide, rounded, flattened seeds are each enclosed in a box-like cell in a legume up to 2 metres long. Widely distributed by ocean currents, the “drift seeds” can survive for so long in the ocean that in Japan the plants are known as modama (“seaweed balls”).

Estuary with Mangroves

Mangrove forests once thrived along coastlines throughout the subtropical and tropical world. Acting as physical protection from storms, the dense roots and shade provide optimal habitat for small, vulnerable marine creatures, especially those not yet ready for a life in the open ocean. Sadly, these forests have been widely degraded and destroyed, and Amami Island is no exception; however, there are protected remnant mangrove forests there, and we were lucky enough to see them up close. From the highway above Kuroshio Forest Mangrove Park, we could see dozens of canoes and kayaks lined up along a beach on one side of the largest intact mangrove area. The canoe rental company advertised guided tours, and I can imagine that languidly paddling through the shaded labyrinthine waterways would be a popular activity in the tourist season. Nearby, we were able to wander the beach immediately above the mangrove zone. Here were growing several familiar plant species, including the sweetly fragrant Pittosporum tobira, Rhaphiolepis umbellata (Yeddo hawthorn) (both shrubby species, in flower) and plenty of Pandanus odoriferus.

A second goal on the island was to locate populations of Acer insulare (island maple) to compare them with other known species in Acer section Macrantha (the “snakebark maple” group) and to obtain samples for analysis. Acer insulare is surprisingly common above about 100 m elevation on Amami, and often found in mixed forests with gigantic (up to 10-m-tall) Sphaeropteris lepifera (syn. Cyathea lepifera) (flying spider monkey tree fern—no, we didn’t see any monkeys, flying or otherwise). Our colleague on the expedition, Ikuyo Saeki, collected fresh A. insulare leaf material for DNA analysis. We also arranged to supply her with material of the Taiwanese A. kawakamii (tail-leaf maple) from the Botanical Garden’s collections to compare. From our observations in the field, it appears that the two are conspecific (i.e., the same species), but we won’t know for sure until her molecular analysis is complete.

Kagoshima and Sakurajima. We were disappointed to learn that Yakushima, our next scheduled stop after leaving Amami, was out of reach, as high winds had closed the airport. Renowned for its ancient trees, the island is also the home of Acer morifolium, another snakebark maple that we were keen to observe in habitat. Stranded at Kagoshima Airport (the intermediate stop), Ryo and Ikuyo eventually found us a hotel where we made plans for the following day. Though Yakushima was not in the cards, the volcanic island Sakurajima, a short ferry ride from Kagoshima, was easily reached. During the circumnavigation of that island (in a rented car), we not only admired the steaming volcano (Sakurajima is Japan’s most active volcano) and a range of plants—including cultivated Ilex rotunda (Kurogane holly), Pinus thunbergii (more on this presently), Podocarpus macrophyllus (Buddhist pine), and Prunus speciosa (Oshima cherry)—but experienced the hospitality of the Sakurajima residents, as well.

Our entirely spontaneous lunch stop was at Café Shirahama, a hole-in-the-wall vegetarian restaurant. This was not only a delicious repast, but a thoroughly entertaining experience, too. It turns out that the proprietress/chef, her husband (an award-winning giant radish farmer), their daughter, and the café were featured in a segment of the 2016 BBC documentary series Joanna Lumley’s Japan (check out Episode 3). Once the café owners learned that Dan was from the UK, they became very animated and excitedly produced a treasured picture showing themselves with the film crew and Lumley. A thoroughly memorable experience, made even more exceptional by the warmth of the people. It was also an opportunity to sample tempura made with just-harvested Equisetum arvense (field horsetail) (it was surprisingly tasty, with a wonderful texture), and a lighter-than-air sponge cake made from radish (!) flour, finished with espresso and an unrefined nugget of cane sugar.

During our travels we saw plenty of damage to Pinus thunbergii; that is, browning and dead tops and branches. Across Asia Japanese black pine is being attacked by a North American parasitic nematode (the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus), which is vectored by Asian longhorn beetles. Older trees, especially those associated with temples and shrines, are apparently routinely treated with systemic pesticides to keep them alive, as infections are nearly always fatal. Near the volcano, the number of dead trees was impressive—almost overwhelming—suggesting that, perhaps, the added stress of a sulfurous atmosphere, or some missing soil micronutrient in the lava- and cinder-based soil might be a contributing factor in their demise. It was puzzling, too, that the vast landscape created by the 1914 eruption is populated by dense forests of P. thunbergii, with a few grasses, but little else, and virtually no other trees.

Gifu Prefecture. We left the relative warmth of Kagoshima Prefecture, and flew northeast to Nagoya, traveling then by train northeast again to Nakatsugawa city in Gifu Prefecture. Although within 125 km of Nagoya and the coast, the climate here was distinctly continental, with freezing temperatures overnight and snow. We were planning to execute another of our “institutional” goals: to collect seed of the spring-fruiting Acer pycnanthum, the Japanese red maple, which is a wetland species that is “threatened” according to the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature).

One of the largest intact populations of A. pycnanthum, in Sendambayashi, is currently faced with the construction of a new high-speed railway line. The proposed development appears now to be going ahead, and the Japanese red maple population, containing at least 74 mature individuals, will be decimated. There was snow on the ground when we visited the site and sleet was still coming down. Acer pycnanthum had not yet opened its flowers. Together with the maple were several Clethra barbinervis (Japanese clethra), Chamaecyparis obtusa (hinoki cypress) and Magnolia stellata (star magnolia). Until I saw them all skirting the waterline, I wasn’t aware that any of these were wetland plants. The property is owned by the Asano family, who have maintained it for generations. Mr. and Mrs. Asano were very kind, inviting us in from the cold into their wonderful home to enjoy a cup of coffee and some homemade peanut brittle. Mr. Asano explained that the house was built by his forebears using hinoki timber harvested from the land on which they continue to farm (currently rice and peanuts), now adjacent to the wetland.

In Iida, across the mountain from Nakatsugawa (and also initially with even more snow on the ground), we were treated to views of a good number of mature individuals of Acer pycnanthum, their flowers beginning to open. Needless to say, nowhere did we find female trees with fruits. Our tour of Acer pycnanthum sites followed a lavish lunch put on by the Japanese red maple conservation group’s founder and president, Mrs. A. Kitazawa. Along the way, we saw stunning examples of Metasequoia glyptostroboides (dawn redwood) and Prunus itosakura Pendula Group (weeping higan cherry)—one specimen more than 300 years old and several at least 100 years old. Later that day, we were invited to speak at a special Japanese red maple conservation group event: Dan on the efforts of the BGCI Global Conservation Consortium for Acer (GCC Acer) (translations by Ikuyo), and me on the Japanese Acer collection at UBC Botanical Garden (translations by Ryo).

Nagoya. As planned, Ikuyo departed for the graduation ceremony at Tsukuba University, and we were sorry to see her go. Her research and contacts were proving to be exceptionally useful, both in our understanding of the state of maple conservation in Japan and her ability to connect us with other researchers, land-owners and conservation groups. She is also fantastically well-organized, resourceful, good-natured and energetic, as well as an excellent interpreter. In other words, a pleasure to have around. Before her departure, she agreed to join us as a steering committee member with the Global Conservation Consortium for Acer (GCC Acer). This was a considerable relief, as we knew she already had plenty on her plate, including a move from the University of Tsukuba to a new position at Osaka University, beginning April 1st.

Dan and Ryo and I proceeded to Nagoya, a sizable city in southern Japan and the capital of Aichi Prefecture, located about 250 km west-southwest of Tokyo. Another of our goals in visiting Japan was to make connections and strengthen ties with local botanical and horticultural institutions. In this regard, Higashiyama Botanical Gardens, which is more widely known as Higashiyama Zoo and Botanical Gardens, was high on the list. The site, established in 1937, is impressively large at 80 hectares (200 acres). It is advertised as one of Asia’s largest attractions with over 550 species of animals (apparently Japan’s second largest zoo), and Asia’s largest collection of plants, with over 7000 taxa. For comparison, UBC BG is about 35 ha with a collection of about 5200 unique taxa (but no lions, tigers or bears).

On the way to the garden, we walked up a commercial avenue bedecked with Acer pycnanthum street trees. The species was also featured prominently on a spacious plaza immediately inside the garden entrance. These plaza trees and those on the streets outside all appeared to be of a similar age, and I assume that the planting-out of a “vulnerable” southern Japanese endemic species probably coincided with the signing ceremonies of the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (a.k.a. the “Nagoya Protocol”). This is a supplementary agreement to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) that was signed in Nagoya in 2010. Higashiyama Botanical Gardens is listed under Cooperation and Partnerships on the CBD website, though I could find no details regarding the partnership.

To be honest, there are far too many details to adequately characterize our visit to the Gardens, but below are a few highlights. Suffice to say that our hosts, Mr. Kazuyuki Ishikawa and Ms. Haruko Sato, both of the Botanical Gardens Green Landscaping Section, made sure that we saw as many aspects of the Botanical Garden as time would allow. First, though, we exchanged business cards (a quintessentially Japanese obligation when meeting professionally), and although seemingly overly formal, the practice is vital for recalling hosts’ names, their responsibilities and contact information (now made nearly effortless by the translation app on my phone). We spent several hours walking the garden. Even avoiding the zoo and amusement park, another of my apps tells me we walked more than 20,000 steps that day.

There were certainly a lot of plants. Some were familiar (including a collection of 1970s-era Pacific Northwest American rhododendron hybrids), and some, not so familiar. Fortunately, labeling seemed mostly good. With translation help from Ryo, our two hosts answered many of our questions. Their responsibilities appeared to be involved with garden development, rather than curation, and that was the direction the tour and conversations tended to go. The newest garden feature (the “Flower Garden”) appeared to have been finished mere hours before our visit. A vast network of paved pathways and planted beds, the centrepiece is a 1000-year-old Olea europaea (olive tree), imported from Spain. The carbon footprint/sustainability aspects of this accession we found somewhat troubling, but that aside, the scale of the construction was impressive.

Acacia covenyi with Sky Tower

Plants of significant note (to me at least) included: the highly desirable (and impossible to grow for us) witch-hazel-relative Rhodoleia championii (Hong Kong rose) in full, glorious bloom and the florally effervescent Australian Acacia covenyi (blue bush). With more time we could have explored the extensive and artfully-presented bamboo collection and the impressive (though mostly not-yet-in-flower) ornamental cherry collection (the “Cherry Corridor”), to say nothing of the zoo, monorail, amusement park and Higashiyama Sky Tower (for dinner and apparently impressive views). The final highlight for me was the tunnel entrance to the garden. It was almost the first thing we saw, but all the more impressive when we re-entered it on our way out of the garden. The spaciousness, welcoming illumination and playful graphics stood in stark contrast to our own tunnel, which, without the visual anchor of the Moon Gate would be an even less-inviting passage (we really do need to do something about that!). Before departing, we all agreed to maintain a dialogue, particularly regarding information about maple collections and conservation.

The following day we visited the Gifu International Horticulture Academy, a horticulture school offering students two-year diplomas in floristry, floral cultivation, and landscape gardening and greening. We toured the facilities with our host, Professor Akira Aida, head of the landscape science department, and were treated to lunch with the school’s director, Yoshitomo Imanishi, together with a few of the staff. Unfortunately, there were few students about, as the winter term had just finished and most were taking a break from school. Both Ryo and I gave short presentations to the staff. Mine was an overview of UBC Botanical Garden, and Ryo’s, the history of Nitobe Memorial Garden.

Cinnamomum camphora

It was hard not to be envious of the well-supplied, modern indoor and outdoor workshops and classrooms, extensive tool selection, state-of-the-art equipment, landscaped grounds and multiple glasshouses and poly-tunnels available to the various programs (and all of this for 40 students). We were duly impressed. My only complaint was having to walk (shuffle, really) through the buildings wearing the obligatory faux-leather indoor sandals, clearly made for Japanese feet. Stairs were the worst: the sandals immediately flew off down the stairs as I fruitlessly tried to grip the smooth vinyl surface with my socked toes. My indoor plant highlight was Albizia splendens (syn. Pithecellobium confertum). The so-called “everfresh” tree is a large tropical tree mostly propagated for use as an indoor foliage plant; it would doubtfully thrive indoors in Vancouver, but this part of Japan is both humid and bright throughout the year. Later that day, Dan and I headed off, in the rain, to Atsuta Jingu, an ancient and very famous Shinto shrine near mid-town Nagoya, where we saw an impressive, 1300-year-old Cinnamomum camphora (camphor tree) in the failing light. Next to it is an open storehouse stacked with sake barrels.

Tokyo (again). We purposefully left time at the end of our mostly maple-focused activities to enjoy the country’s famous cherry trees. The end of March is the usual time for sakura (flowering cherry) viewing in Tokyo and Ryo had made significant efforts and arrangements for us to visit the preeminent scientific cherry collections in the area. Alas, the winter was both cold and especially wet, and the Tama Forest Science Garden (our first scheduled visit) had suffered considerable snow damage, which necessitated repairs and closures. Ever resourceful, Ryo quickly arranged for a visit to Jindai Botanical Garden, part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association’s network of parks and gardens. Jindai is noted for its cherries, but also for its world class camellia collection, and stunning conservatory complex. Here, we were met by Jindai’s director, Mr. Teruki Matsui, the cherry researcher Mr. Keiichi Higuchi, and our old friend Professor Makoto Suzuki.

It was raining, sometimes very hard, and it was cold. Not exactly the best weather for a tour. As noted, the cherries were well behind schedule; however, we did manage to see a few early cherry selections, including Prunus itosakura ‘Jindai-Akebono’ and a magnificent Prunus jamasakura (Japanese hill cherry), as well as the camellia collection (at least from the perimeter) and a few maples. We finally took refuge in the conservatory, which was delightfully uncrowded (there were very few visitors anywhere in the garden). Several notable exhibits—orchids, begonias, waterlilies and Chilean plants—were well-interpreted and labeled. There were a few stand-out plants, including an Aristolochia salvadorensis (Darth Vader flower), which has both unusually shrubby stems (unusual in that nearly all aristolochias are vining plants) and extraordinarily weird flowers produced on horizontal stems along the ground. A handsome Strongylodon macrobotrys (jade vine) was at its peak and beautifully displayed. Maybe it was just that we were out of the rain, but my overall impression was of excellent management of both the plants and space. This, and the rest of the garden would be a high priority on a return schedule, should that opportunity arise.

For our next visit the following day, the weather was close to perfect. Yuki Farm and Cherry Blossom Garden boasts some 400 mature planted sakura (flowering cherries) on an approximately 8-ha (20-acre) site, which includes an area of prepared ground where they produce upwards of 1000 cherry trees annually. Only 60 km north of Tokyo near Oyama city, it should have been overrun with visitors at the end of March, but the oft-mentioned delay in sakura flowering worked to our advantage. Granted, there were precious few flowers to enjoy, but there were definitely other draws, and no crowds of people, nor clogged roads reaching the farm. We were joined for the day by an old friend, Dr. Eijiro Fujii (Japanese garden historian, plant scientist and Ryo’s graduate supervisor at Chiba University). Professor Fujii, whose command of English is excellent, conducted research on plant shape preferences (UBC students were the subjects) a few years back, and is well known in Japan as an advocate for best practices in arboriculture. Needless to say, we were honoured and pleased to have him with us and had no difficulty engaging with him on a variety of dendrological subjects.

Yuki Farm & Cherry Blossom Garden

Our hosts, Mr. Mitsuru Tasaki (the farm manager) and Ms. Yuiyo Kimura, gave us an overview of the site and showed us their extensive and exceptionally tidy production facility, where cherry trees are propagated and grown to size before being sold or otherwise dispersed. This was of significant interest to me, as we are engaged in producing cherry trees at our own Botanical Garden Nursery. Besides, I have an insatiable curiosity when it comes to learning about especially traditional Japanese propagation methods and techniques.

I could have spent another few hours with Mr. Tasaki discussing production techniques, but our time was limited and there were actually a few flowers to look at before our taxi ride to the train station. Most impressive (perhaps surprisingly) was an American cultivar, ‘Pink Cloud’, which is thought to be a hybrid of P. speciosa and P. campanulata that arose spontaneously at the Huntington Botanical Garden in San Marino, California. Yuki Farm and Cherry Blossom Garden is an official site of the Flower Association of Japan, but owned by the gigantic industrial machinery manufacturer Komatsu, which is a significant employer in the Oyama city area. According to our hosts, Komatsu doesn’t want to advertise the fact that they are involved, but it’s clear that someone is underwriting much of the activity. I asked whether they made a profit selling trees and they laughed at the question.

To save time, and because it was an option, we decided to take a Shinkansen (bullet train) back to Tokyo. This took only a few minutes. A 60-km journey doesn’t take long at 300 km/hr. We were headed to Kobayashi Kojuen (Maple Tree Garden), a specialty maple nursery, in Kawaguchi on the outskirts of Tokyo. There, we were met by the proprietor, Kento Yoshioka, an affable young man who spoke and acted with a kind of confidence about maples and propagation that would have you believe he’s practiced the trade since he could hold a grafting knife (which I believe he has). His bona fides fit the picture, too. His direct ancestors have been producing maple trees for sale on the property since the Edo Period (i.e., between 1603 and 1868, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate). There were countless trees in all sizes in seemingly endless rows and blocks. Although they were barely leafing out, it was clear that there were scores of different cultivars. I asked why there were no labels, then immediately regretted the question. He looked puzzled, then explained (in Japanese) that he had no need of labels as he knew all of his plants. Of course, he would. We finished the day with an excellent meal generously hosted by Dr. Fujii at a lively Japanese restaurant near our hotel in the Shinagawa District. I was treated to three different kinds of sake—a telling taste experience. I still prefer beer.

Dan departed our last day in Tokyo from Haneda Airport, which is a relatively short train ride from Shinagawa. Ryo and I then proceeded to find lunch and a suitable activity that would fill the time until the journey to Narita Airport and my departure later in the afternoon. We settled on Hama-rikyu Gardens in the Chuo ward of Tokyo, where the Sumida River empties into Tokyo Bay. A spacious park, its most striking feature is the surrounding cityscape: grand, shining office towers on all sides. The landscape is mostly low rolling hills and acres of still-dormant, straw-coloured grass, punctuated with groups of pines and still bare-branched cherry trees, conveniently hung with wooden signs bearing names and descriptions in both Japanese and English. I doubt I’ll ever get used to seeing lawns that dead-looking in March, especially when Vancouver is so green at the same time.

Prunus speciosa (Possibly ‘Hosokawa-odora’)

This garden is famous, not just for being a green (er, yellow-brown) oasis in the middle of the city, but because of its history. Designated a Special National Historic Site as well as a Special National Place of Scenic Beauty, the garden dates from the mid 17th century, when it was a Tokugawa villa, garden and hunting park. Not surprisingly, there are excellent views across ponds, but the large network of paths sometimes lead to unexpected views. A tidal pond connects with the sea through a wide gap on the east side of the garden—the whole property is surrounded by a salt-water moat, filled by the waters of Tokyo Bay. One path presented a very strange sight that day: a large yacht appeared to be moored in the Garden. Later, we stood next to a weir close to the dock from which the various generations of Shoguns boarded their boats, where we watched a school of large fish, including a dinner-plate-sized skate, crowding the gate. They were clearly waiting for someone or something to release them into the Bay. A large field of mustard (in stunning full flower) appeared along another path and there was even a sublimely beautiful, blooming cherry tree by a bridge. It was unlabeled, but fragrant, with semi-double white flowers. I pegged it as a selection of Oshima cherry, perhaps Prunus speciosa ‘Hosokawa-odora’. I overheard a woman standing near it speaking in English, so asked if she didn’t agree that it was a beautiful tree. She said she’d come to Japan from Vancouver to see cherries (“where are they”? she demanded). I told her that both Ryo and I were also from Vancouver and that I hoped she came to Japan to stay for somewhat longer, if it was cherries she came to see. Otherwise, she’d be better off going home to see them. So, I took my own advice, but it was time for me to go, anyway.

Here I sit, contemplating cherry blossoms at home, but I can’t not think about that tiny, vulnerable hillside of Acer amamiense. One good typhoon, earthquake or tsunami and the whole population could be lost. Or the valiant, tireless efforts of a volunteer group bent on protecting the Japanese red maple and its wetland habitats, up against the relentless juggernaut of development. We met with people who want to help conserve plants and a few who are making progress in conservation happen. To continue to do that we have to connect with people across the botanical garden, government, academic and community group worlds, and we don’t have a lot of time to waste. I think we’ve made an excellent start.

- Zelkova serrata

- Yuki Farm & Cherry Blossom Garden

- View from Acer amamiense habitat

- Ternstroemia gymnanthera

- Taxus cuspidata

- Stachyurus praecox var matsuzakii

- Sphaeropteris lepifera

- Sake Barrels

- Rhodoleia championii

- Rhododendron scabrum

- Rhaphiolepis umbellata

- Prunus jamasakura

- Prunus itosakura PendulaGroup

- Platanus x hispanica

- Pinus densiflora Umbraculifera

- Pandanus odorifera

- Olea europaea

- Mustard

- Mrs. Kitazawa

- Magnolia denudata

- Magnolia denudata

- Institute for Nature Study

- Ilex rotunda

- Higashiyama Botanical Garden tunnel

- Hamarikyu Gardens

- Erythrina speciosa

- Deutzia naseana var naseana

- Daphne odora

- Cyrtomium falcatum

- Cycas revoluta with seed

- Cemetary with Codiaeum variegatum and Cordyline frutocosa

- Aristolochia salvadorensis

- Alpinia zerumbet Variegata

- Acer pycnanthum

- Acer amamiense seedling

- Acer amamiense female

- Entada phaseoloides

- Podocarpus macrophyllus

- Pandanus odorifera

- Prunus campanulata

- Lunch at Café Shirahama

- Pinus thunbergii bark

- Sign on power pole

- Skate

- Shinkansen

- Sphaeropteris lepifera roadside

Submitted by: Douglas Justice, Associate Director, Horticulture and Collections